Hey Gabe.

(In response to this blog.)

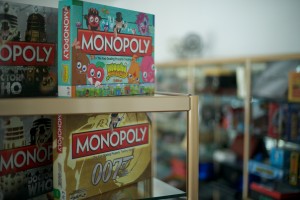

A couple years ago I launched my first board game. It was a success with Kickstarter and the critics, but not the marketplace. These are the lessons I learned from that first experience. It’s what I keep reminding myself as I test the next batch of prototypes.

This is what I’ve got to say, one first-time-and-out-the-other-side designer to you, in the middle of your first time. This isn’t the masterclass. It’s not the stuff that’ll make all the difference once you have the basics down. It is the basics. The stuff you want someone to tell you first.

The Most Important Thing

Simplify.

You’re a veteran of many games, and odds are, your instinct is to make a Gamer’s Game: Something rich and deep with layers of nuance that are revealed play after play. Games that anybody can master in five minutes rarely hold your interest.

The thing is, it’s really, really hard to write a game like that in a way that new players will get into. Especially coming at this with a background of computer games, where the mechanics are handled for you. And roleplaying games, where having a shelf of books with bonus mechanics to dive into when you’re ready is a plus. For board and card game, engaging with the mechanics is the play. If a player can load that ruleset into their head without confusion, they’ll enjoy their first play and come back for more.

So be merciless. Trim elements from your game until you find the minimal heart of that sparks the fun, with every other element set to the side. Once you’ve found that, you can start putting the trimmed elements back in, one at a time. You’ll see which ones give you the most bang for your buck, and which ones are the stumbling blocks for new players.

You can always make it more complex in an expansion. There will be game mechanics that you love, but that new players stumble on. Those can come back later, once your player has mastered the core game and they’re hungry for more. With your audience, you won’t even have to wait: You can bundle expansions as stretch rewards that your Kickstarter campaign is sure to hit.

Brace Yourself

Your game is already more complex than you know. The coming step – making your game ready to play without you there to teach it – is going to rub your nose in it. Be ready, ‘cause the next section of development can be a slog if you don’t force it to stay fun.

First off, writing everything down is going to point out every assumption you made about what the players already knew, and how much harder it is to explain things in a one-size-fits-all rulebook. The silver lining is, when you’re not there, the players don’t get to interrupt you for explaining things. You get to set the training down in Your Ideal Way.

Part two of why this step wants to be a slog is the criticism. Starting from “We couldn’t understand it” and working your way up to “There’s a contradiction on page 7”, this step is all about reacting to negative feedback. Not inherently fun.

Turns out, writing a game down well is nearly as much work as inventing the game in the first place.

Rules You Can Break

One you should, one you shouldn’t.

The Rulebook Should Take As Much Work As The Game

Or for you, maybe not.

You can hand this one off to a pro. Normally a new designer starting out would be stuck with this step, but you’ve already got the industry contacts that developer-publishers will line up to polish your game and get the publishing contract.

Taking critique on your writing is hard when it’s your game, your baby. But hand it off to another developer and it’s a job with problems to be solved. They don’t have your emotional investment, and they’ve leveled up from doing this many times before. Of course, they’ll want a cut. A big one. But you’ve got leverage to negotiate with and having someone else handle the steps going forward will free you up to get back to design.

The Printing Cost Should Be 15-20% of the MSRP

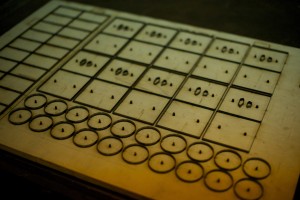

That’s the rule of thumb for the hobby game industry. There’s so much more to say about this, but that’s the short version. What you need to know as a designer is that every part adds up. Every card, every punchboard, every die-cut-pattern, every bit. Once you’ve written your own game, you might start to marvel at the economy of components that hit games are made with.

There’s a couple ways you can estimate the costs of your game.

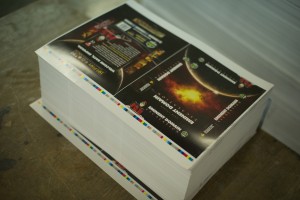

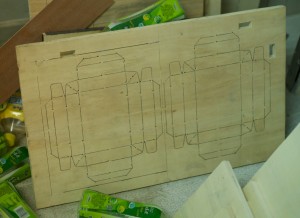

The first step, either way, is to figure out exactly what parts have to be made. Clear off a table. Unbox your prototype completely and set it into piles: board, cards, tokens, wooden/plastic parts. Write down that list. Remember the other parts that aren’t in your playtest kit yet: The rulebook and box liner. And the box.

Step two, version one: Find a game in your collection with nearly identical or slightly more components. Your MSRP will be about the same as its.

Step two, version two: Fire off a letter to a printer with your parts list, and ask for a quote request in two versions: 2,000 and 5,000 copies printed. 2,000 is a normal size first-print for a hobby game, to test market reception. 5,000 is a healthy size reprint for a game that the market has picked up.

For a first print quote request, I’d recommend Ludofact of Germany. They’re great about breaking the print quote down by parts, showing you what is adding to the cost of your game. And they’ve printed more than half the Spiel des Jahres winning games of the last 30 years: They’re proven veterans.

With a quote like that in hand, you can go back and take a second serious look at which parts of your game are the core, and what parts are delivering the most fun in the space remaining.

Now the 15-20% rule is one you can break: With your audience and the interest you’ve built blogging about this game for more than a year, your game should Kickstart strong enough to justify a 5,000+ copy print run immediately. That’ll lower your per-copy-cost below what a publisher could normally plan around.

Also, the 15-20% rule is built on the economics of selling publisher to distributor to brick&mortar merchant. (Optional extra step: Add “fulfillment house” in between publisher and distributor.) For your Kickstarted batch, you’re selling direct to the customer. Your leftover profit margin is much higher. You’ll be tempted to expand the game back to it’s full original version, with all the stuff you had to cut.

Don’t.

That margin is your bankroll for keeping your game in print, and adding stretch rewards for your backers. These bonus rewards can be expansions for later buyers, or convention giveaways, or other promo items. You’ve made it this far with the core game simple. Keep it simple! If you build the core game to the point that the economics only work with a 5,000 copy print run and direct-sales-to-buyers, then you’ll have a devil of a time keeping it in print after the KS campaign is done. You’ll also be no friend to the hobby stores that you’d like to carry your game. If your economics still work with 2,000 copy print runs, your bases are covered for most any future.

So that’s it: Tabletop Game Design for Publishing, the Going From Alpha To Beta, What I Wish Someone Had Told Me.

No, wait, one last rule. The most important one.

Keep having fun. As long as you’re still having fun, you’ll keep at it ‘til it’s right. As long as you keep having fun, you’ll take a 20 on your roll.

Keep up the good work.